In June 2020 I received an email from Diana Story. She introduced herself as “an Australian critical heritage studies student, living in the Netherlands,” and distant relative of Paul Julien. Diana’s grandfather, in Dutch referred to as ‘opa’, was a cousin of Julien’s who migrated to Australia. In a combination of these capacities she had, as part of her studies, written a response to my letter to Paul Julien that was published in Trigger, the magazine of Fotomuseum Antwerp.[1]Stultiens, A. (2020, December 14). Trigger magazine | A Letter to Dr. Paul Julien. FOMU. … Continue reading She generously shared this response with me and added some questions to it in relation to her interest in trauma-informed heritage practices. I invited Diana to develop her text further for the Reframing PJU platform. That led not only to this publication but also to the embedded research Diana is preparing as a graduation project of her MA studies. I look forward to more contributions from her that will, in time, also be made available.

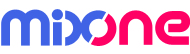

[2]Illustration (based on a roll film filed as PJU-657) with the interview quoted below. Personal collection.

[2]Illustration (based on a roll film filed as PJU-657) with the interview quoted below. Personal collection.

Familial Reckoning

by Diana Story

As an emerging museum and heritage researcher, I discovered Andrea Stultiens’ letter to Dr. Paul Julien in Trigger magazine in October of 2020, during research for a critical heritage studies Masters course I am currently undertaking.

In the aim of transparency from writer to reader, as well as to give context to the gaze through which this response was written, it feels important to disclose some information on my background. Born in Naarm (often referred to by the colonial name of Melbourne), I grew up on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation. Raised by parents from diverging socio-economic backgrounds and cultures brought along with it a reality of descending both from persons who profited from and actively participated in British and Dutch colonial regimes, as well as to individuals who were oppressed by colonial systems. In admiration of and solidarity with museum critical race theorist Dr. Porchia Moore’s use of an intersectional approach to outline their personal positionality,[3]Death to Museums. (2020, August 1). Death to Museums August Series: Saturday [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1VYXnZvl27Y I will do the same. I am a white Australian cisgender woman of intercultural background in my twenties, a student, artist and heritage practitioner.

After graduating art school I spent the early part of my twenties working at the nation state’s oldest art museum, The National Gallery of Victoria. As a collection of the state of Victoria, the institution’s name reveals its colonial origins. Every now and then I received questions about how it came to contain the word ‘national.’ I would explain that the museum had been founded before Australia’s federation as a nation-state and its name had remained unchanged since. Despite my situationality, as a museum worker upon unceded land and moreover, as a direct descendent of perpetrators of imperial violence, my understanding of coloniality was extremely limited, one-dimensional and almost entirely disconnected with present-day realities. When I thought about coloniality, I remembered my mother’s voice warning me not to look too deeply because I would be horrified as to what I would find. What little knowledge I had about First Nations persons, cultures, contemporary life and history came entirely from white Australians during one school term, aged twelve. When mid-2000s Victorian school curriculum taught that Australia was ‘discovered’ by James Cook, my Opa would scoff and counter proudly that the true ‘discoverer’ was a Dutchman.

In late 2018 I left Australia, driven by a desire to learn about cultures beyond those of which I had grown up within. This movement in location ignited a consciousness towards the presence of material wealth surrounding me that I had never had during my life in Australia. Visiting nation states which had engaged in European expansionism and imperialism, as well as those lesser implicated in such campaigns made me become more curious about how historical actions continue to influence the current day. Could contemporary power and wealth distributions be delineated more transparently if we looked more realistically to the structures our ancestors existed within? Furthermore, being distant from Australia made me begin to question what I knew to be ‘history.’ I wondered about the validity of dominant historical narratives. Who created and entrenched these narratives? What purpose do they serve? Who do they occlude? Who do they empower? During more recent admission to a critical heritage studies course with a syllabus which introduced students to decolonial literature and interventions, as well as Macdonald’s concept of ‘past-presencing,’[4]Macdonald, S. (2013). Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today (1st ed.). Routledge. I was encouraged to explore my own personal positionality. By reflecting on the microculture of my own family I hoped to gain some understanding of the legacies of their actions, historically and today, as well as their positionality and the structures they supported and benefited from. It is via this process that I came across Stultiens’ Trigger article.

As a younger cousin of Paul Julien my Opa had grown up listening to stories of Julien’s travels and ideas of individuals he met. After the Second World War my grandfather migrated to Australia, carrying within him the stories of his cousin and an interest in Julien’s literature that continued into my Opa’s later years. Stultiens begins by introducing Dr. Paul Julien: a chemist with an interest in anthropology. She positions the vast quantities of his photographic work held in current Dutch museum collections alongside his practice of collecting human measurements in the name of scientific research. Stultiens problematises the ethical underpinnings and embodied realisations of Julien’s work, locating intertwining factors and entanglements which may have shaped his motivations and upheld his manner of seeing and acting.

I felt personally touched by her decision to take present-day accountability for the legacies of Julien’s work. In particular for her desire to counter and disrupt the dominant euro-centric patriarchal gaze embedded within the work and its production, the accompanying narratives and, indubitably, Julien’s personal belief system. As I became more conscious of Julien’s presence on Dutch radio and his role in crafting and disseminating imagerial and ideological perspectives and impressions of those he met during his research trips, the more unsettled I became. I thought about the power dynamics of the colonial structures he moved within which readily stripped an individual’s agency for self-representation to exclusively propagate narratives produced by a white male gaze. By looking to understand the realities of those oppressed by the colonial systems which concurrently gave rise to Julien’s celebrated career, Stultiens’ desire is to build additional meanings the photographs Julien produced from the perspective(s) of the persons who were ‘studied.’

Stultiens included two primary text sources, translated from Dutch to English.[5]These are the quotes referred to: Excerpt from a radio lecture by Paul Julien, broadcasted in 1933 by the KRO [Catholic Radio Broadcaster]: Gbarnga is an economic hub … with a level of activity … Continue reading Reading Julien’s recollections on his research in Liberia disturbed me. What emerged was:

- A use of power systems and positionality to force submission for ‘research’ purposes.

- The normalisation of violence as a tool to achieve ‘research’ pursuits.

- The fact that white persons could select whom they wanted to study, that the personal rights of the persons they wanted to study were unquestionably overridden by their desires.

- The resistance of the African ‘villagers’ to Julien’s research and the collective action to evacuate the village.

- Julien viewing the persons he studied as intellectually inferior: ‘they would not understand my true interests…’ Using this to justify his non-transparent practice, Julien asserted that this strategy allowed him to medically assist ‘many people.’

At this point, I remembered something my Opa had once said about Julien, ’he was a good Catholic.’ Thinking about his conscious decision not to explain the context of his research to those whom he studied, it seemed possible that Julien was motivated by and complicit in white-saviour complexes, especially considering the dominant role of the Catholic Church throughout colonised nation states of continental Africa. I came across another text that mentioned his involvement in emergency baptisms. In Catholic catechism, this form of baptism can be performed by lay persons when persons are considered to be at close risk of death.[6]Catholic Church. (n.d.). Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText. The Holy See. Retrieved September 8, 2021, from https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P3L.HTM It is important to note that the circumstances in which someone is considered in proximity of death are entirely at the discretion of the individual performing the baptism.

But what kinds of experiences did the people whom Paul Julien met have? What sorts of feelings did they have about being ‘studied’? How did his presence contribute to the impacts of European colonisation in Africa and their legacies? I thought once again of the fleeing of the entire village in Liberia. My mind returned to something Jennifer Tosch mentioned during the Amsterdam Black Heritage Tour I attended as a part of my coursework. Thinking about Bourdieu’s notion of habitus,[7]Routledge. (2016). Habitus | Social Theory Rewired. Social Theory Rewired. http://routledgesoc.com/category/profile-tags/habitus I remembered how Tosch spoke of unconscious physical reactions during intercultural interactions. She proposed that aesthetics of whiteness can be embedded in the memories of Black persons as symbolic of terror. The possibility emerges that this memory of association may evoke physiological reactions of fear.[8]Tosch, J. (n.d.). Welcome to Black Heritage Tours — Home for Black Heritage Amsterdam Tours in Amsterdam & Black Heritage Tours in New York. Black Heritage Tours in New York & … Continue reading

Tosch also spoke of a white tour attendee who admitted that she subconsciously clutches her bag closer to her when in the presence of Black persons. In the second instance, I wondered about the kinds of messaging about Black persons the tour attendee had absorbed from her family and from the society she was raised within. Stemming from these thoughts I found myself questioning the extent of which Julien’s narratives had influenced my Opa’s ideas on race. Two years after his migration from the Netherlands to Australia he became the stepfather of my grandmother’s first son, whose biological father was Nigerian. In my experience, my Opa was quietly revered in the family setting to have married a woman with a Black son born out-of-wedlock. As I grew to be a teenager I came to learn more stories about the family dynamic. Ethnicity and skin colour was never spoken about until my uncle started school and other children asked him why he was a ‘different’ colour to them. When he returned home, both of my grandparents refused to answer any questions, insisting that my Opa was my uncle’s father and that was all he needed to know. This later led to confusion from my father and their other siblings who also didn’t understand why their brother looked different to them. One evening my grandmother revealed to me that she had hidden my uncle’s ethnicity until my grandfather had proposed. When my Opa discovered that his son was not ‘half-Maltese’ but half-Nigerian, he furiously insisted that my uncle be adopted out. My grandmother refused, they went on to marry and my Opa went on to receive admiration until his death as being of ‘strong moral character.’[9]A point of departure for future research includes the mapping of multi-actor positionalities within my family dynamic and exploring the influence of values and perspectives held by individuals and … Continue reading

I started to think more and more about what drove people like Julien to do the kind of research they did. What kinds of motivations did they have? In the case of Paul Julien, was he driven by the white saviour mentalities perpetuated by Catholic institutions? Through a genuine drive to bring medical aid? From a personal (and privileged) desire to be seen as a kind of cosmopolitan world traveler? I began to reflect on the tacit nature of habitus and the intergenerational transfer of qualities and actions that we might venerate, admonish or exist unaware of. To this end, I began to question the origins of my personal exaltation of the cosmopolitan.

If the subconscious is influenced not only by memories from personal lived experience but also that of our ancestors, it is impossible to imagine the terror residents of Gbarnga may have felt fleeing Julien’s impending visit in 1932.

In her open letter, Stultiens refers to Julien’s repetitive chastising of the persons he studied as ‘rude, primitive or dishonest.’ I admire that she challenged him to think about if his behaviours could be perceived in the same way by those he criticised. It spoke directly to the violent reverberations of eurocentrism.

Reflecting on her experience at a Liberian government press conference, Stultiens wondered about the ongoing influence of colonial legacies in the present-day. Stultiens remembered a government official’s repetition of the phrase ‘you should not be afraid of the health workers because they too get sick,’ during the Ebola pandemic. She further proposes that the very need for such a tactic stems from colonial legacies left by individuals like Julien.

Could similar memories of violence to those held by the people of Gbarnga in 1932 continue to live on in the minds of present-day Liberians?

Stultiens reacted to the problematic nature of Julien’s practice by actively ensuring that she is transparent about her intentions and reasons for research which each person she speaks with. In addition she raises questions of how objects of shared heritage generated under colonial systems should or could be reckoned with in the current day. She also raises issues of offensive language, which made me think of the intervention countering this problematic heritage. Taking the form of an online open source document it asserts that decolonising language should not be seen as something possible to ‘complete’ but rather as an integral element of a continuous ideology to guide heritage practices.[10]Modest, W., & Lelijveld, R. (2017). Words Matter. Research Center for Material Culture. https://www.materialculture.nl/en/publications/words-matter

How can multiperspectivity be added to such heritage? How can we take accountability for our ancestors’ complacency or active participation in systems of coloniality and white supremacism? How could examples of the problematic nature of Julien’s research help us recognise the remnants of colonial-thought structures that linger in our own minds and imaginings of cultures other than our own? Interdisciplinary activism calls us to move beyond the decolonization of institutions and academia and to ‘decolonize our minds’.[11]Heinrichs, M. (2020, August 9). What Does It Mean To Decolonize Your Mind? Organeyez. https://organeyez.co/blog/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-your-mind How might conceptions and behaviours of habitus be actively reprehended before we imbue them into how we treat heritage materialities such as those produced by Julien? Could the documents that Julien produced ever be de-enmeshed from the religious and colonial structures that guided their creation? At the time of writing, my understanding of what heritage ‘object’ might encapsulate is wide in breath. Tangible or intangible in material embodiment, a heritage object is interwoven with qualities of experientiality, transmission, temporal relationships and meaning-making. Thinking about this made me wonder about how the scope and impact of the (im)materiality Julien engendered might be demarcated.

Drawing upon the literature from the course syllabus, the actor-network theory of anthropologist Bruno Latour comes to mind, in which the notion of dynamic constellations are introduced.[12]Latour, B. (2017). On Actor-Network Theory. A Few Clarifications, Plus More Than a Few Complications. Philosophical Literary Journal Logos, 27(1), 173–197. … Continue reading This concept can be used to map the standpoints, meanings and values of multiple actors. In a more object-oriented text, Basu’s concept of ‘in betweenness’ introduces a harmonious concept, proposing that objects exist in an ongoing state of flux that is intersected and influenced by sporadic interchange.[13]Basu, P. (2018). The Inbetweenness of Things: Materializing Mediation and Movement between Worlds. Bloomsbury Academic. It is a term that encompasses multi-dimensionality and suggests constant reshuffling of the coexistence of multiplicities and contradictions. Both Basu and La Tour suggest that tracing the lines between objects and the qualities attached to them by multiple actors could be a useful strategy to identify points of interconnection, divergence and how specific qualities or meanings became attached to objects. Basu exemplifies a singular heritage object and reveals it as holding a multitude of meanings, defiant to one-dimensional definition or categorization. By identifying attributes of this object’s materiality, the agendas assigned to it and its geographic movement, Basu evidences impacts of intercultural exposures upon the inception of materiality and in some cases, its political weaponization.

In an article dissecting trajectories of museological cataloguing practices, Turner argues that humans and objects exist in affective relationships.[14]Turner, H. (2016). Critical Histories of Museum Catalogues. Museum Anthropology, 39(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12118 Within this context, material heritage is subjected to encoding by its perceiver who projects upon it their individual associations of knowledge, value and meaning. Should habitus and self-projection influence how we determine an object’s meaning, ideas around the affective agency of the material ‘object’ itself also seem important to consider. Hoskins asserts ‘things have agency because they produce effects, because they make us feel happy, angry, fearful, or lustful,’[15]Hoskins, J. (2006). Handbook of Material Culture by Tilley, Christopher Published by SAGE Publications Ltd (2006) Paperback. SAGE Publications Ltd. while Basu proposes that object agency can occur in a spiritual sense. Considering Appadurai’s influential theory that materiality can be explored in terms of life-cycle suggesting that objects might be questioned, as you could a human, on their experiences, trajectories and the actors they have intersected with, the possibilities of just how the objects Julien produced might be engaged with feel vast.[16]Appadurai, A. (1988). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

The realisation of each of these scholarly concepts; their similarities and differences, strengthens the notion that material heritage does not have a fixed state. Its interpretation is largely correspondent to the individual, collective and intercultural associations that are attached consciously and unconsciously to heritage objects and are indubitably temporal, tenuous and deviational. A common thread running throughout each of these texts, as well as the earlier mentioned interdisciplinary activist movements, is the confirmation of the reality of multiperspectivity and the need to shift away from singular narratives. Examining our personal identity in an intersectional sense and critically enquiring as to how this may influence what we attach to heritage materialities seems crucial to any step ahead with work like Julien’s.

[17]Governmental press conference, July 15, 2014, Monrovia, Liberia. Photographed by Andrea Stultiens

[17]Governmental press conference, July 15, 2014, Monrovia, Liberia. Photographed by Andrea Stultiens

References

| ↑1 | Stultiens, A. (2020, December 14). Trigger magazine | A Letter to Dr. Paul Julien. FOMU. https://fomu.be/trigger/articles/a-letter-to-dr-paul-julien-pondering-the-photographic-legacy-of-a-dutch-explorer-of-africa |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Illustration (based on a roll film filed as PJU-657) with the interview quoted below. Personal collection. |

| ↑3 | Death to Museums. (2020, August 1). Death to Museums August Series: Saturday [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1VYXnZvl27Y |

| ↑4 | Macdonald, S. (2013). Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today (1st ed.). Routledge. |

| ↑5 | These are the quotes referred to:

Excerpt from a radio lecture by Paul Julien, broadcasted in 1933 by the KRO [Catholic Radio Broadcaster]: & Excerpt from an interview with Julien published in illustrated magazine Katholieke Illustratie in 1960: |

| ↑6 | Catholic Church. (n.d.). Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText. The Holy See. Retrieved September 8, 2021, from https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P3L.HTM |

| ↑7 | Routledge. (2016). Habitus | Social Theory Rewired. Social Theory Rewired. http://routledgesoc.com/category/profile-tags/habitus |

| ↑8 | Tosch, J. (n.d.). Welcome to Black Heritage Tours — Home for Black Heritage Amsterdam Tours in Amsterdam & Black Heritage Tours in New York. Black Heritage Tours in New York & Amsterdam. Retrieved September 8, 2021, from http://www.blackheritagetours.com/ |

| ↑9 | A point of departure for future research includes the mapping of multi-actor positionalities within my family dynamic and exploring the influence of values and perspectives held by individuals and communities they intersected with. It might look toward tracing structural prescriptions of morality, how these transliterate within social cultures of specific localities and their impact upon the individual psyche. |

| ↑10 | Modest, W., & Lelijveld, R. (2017). Words Matter. Research Center for Material Culture. https://www.materialculture.nl/en/publications/words-matter |

| ↑11 | Heinrichs, M. (2020, August 9). What Does It Mean To Decolonize Your Mind? Organeyez. https://organeyez.co/blog/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-your-mind |

| ↑12 | Latour, B. (2017). On Actor-Network Theory. A Few Clarifications, Plus More Than a Few Complications. Philosophical Literary Journal Logos, 27(1), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.22394/0869-5377-2017-1-173-197 |

| ↑13 | Basu, P. (2018). The Inbetweenness of Things: Materializing Mediation and Movement between Worlds. Bloomsbury Academic. |

| ↑14 | Turner, H. (2016). Critical Histories of Museum Catalogues. Museum Anthropology, 39(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12118 |

| ↑15 | Hoskins, J. (2006). Handbook of Material Culture by Tilley, Christopher Published by SAGE Publications Ltd (2006) Paperback. SAGE Publications Ltd. |

| ↑16 | Appadurai, A. (1988). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑17 | Governmental press conference, July 15, 2014, Monrovia, Liberia. Photographed by Andrea Stultiens |